Chapter 1: Introduction (pages 3-16)

Summary in haiku form

Summary in one paragraph

TBD

Notes on specific pages

Pages 4-5: The division between micro and macro is not always clear, e.g., you can study international trade from a micro perspective (treating two countries just like two individuals) or from as macro perspective (for example, dealing with exchange rate issues or distributional issues). Nonetheless, there is a rough dividing line between micro and macro, perhaps best described (to paraphrase P.J. O’Rourke) as being that microeconomists are wrong as specific things and macroeconomists are wrong about things in general.

Page 6: Providing “microfoundations” for macroeconomics has been a major goal of the past few decades of economics research. It’s easy to say that there’s unemployment during a recession, but how do you get that to match up with what microeconomists say about prices adjusting to balance supply and demand? We’ll return to this in chapter 2.

Page 8: A good read to compare life today with life a century ago is the section on “life in the bad old days” from Gordon 2000 (“Does the ‘new economy’ measure up to the great inventions of the past?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 4:49-74): “The urban streets of the 1870s and 1880s were full not just of horses but pigs, which were tolerated because they ate garbage… Added to putrid air was the danger of spoiled food—imagine meat and poultry hung unrefrigerated for days, spoiled fruit, bacteria-infected milk, and so on. Epidemics included yellow fever, scarlet fever, and smallpox… In 1882, only 2 percent of New York City’s houses had water connections… Rural life was marked by isolation, loneliness, and the drudgery of fireplace cooking and laundry done by musclepower… Coal miners, steel workers, and many others worked 60-hour weeks in dirty and dangerous conditions, exposed to suffocating gas and smoke… Sewing in a sweatshop might have been the most oppressive occupation for women, but was not as dangerous as soap-packing plants or the manual stripping of tobacco leaves.” More on infant mortality is in CDC 1999; and Yes, the wheel does apparently date back to about 5,000 BCE.

Page 8: The full title of Adam Smith’s surprisingly readable Wealth of Nations (1776, full text here) is An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

Page 10: Apparently “macroeconomics” (at least as a term) did not come into being until 1933, i.e., the aftermath of the Great Depression. Also, the famous quote from John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946, last name rhymes with “trains”) comes in chapter 3 of A Tract on Monetary Reform (1923): “But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead.”

Page 11: The “dentist” quote is a paraphrase of Keynes: “If economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people, on a level with dentists, that would be splendid!” (I haven’t confirmed this quote, but apparently it comes from John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Persuasion, New York: W.W.Norton & Co., 1963, pp. 358-373.) Among others, the quote appears in a thoughtful essay by Greg Mankiw (“The macroeconomist as scientist and engineer“, 2006) on teaching and practicing macroeconomics.

Page 12: The racehorse line is adapted from the famous quote about Secretariat, who won the Triple Crown in 1973 with a stunning 31-length victory at the Belmont Stakes. (Watch the race here; the call by Chic Anderson includes the line that “Secretariat is moving like a tremendous machine!”) The “best of all possible worlds” quote is from Voltaire’s Candide.

Chapter 2: Unemployment (pages 17-30)

Summary in haiku form

Summary in one paragraph

TBD

Notes on specific pages

Page 17: This is a joking reference to the “busy as bees” line on page 7, and also to a 1980s TV ad for Kellogg’s Nut and Honey Crunch cereal.

Page 18: The estimate of 25% unemployment in 1933 comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, but data before 1940 are sketchy. A nice graphical estimate of historic U.S. unemployment rates (back to 1890) is here.

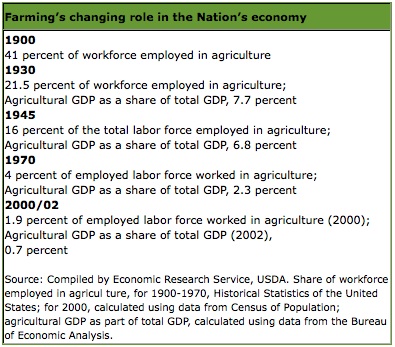

Page 20: Regarding agricultural employment, here’s some amazing stats from USDA’s The 20th Century Transformation of U.S. Agriculture and Farm Policy (Electronic Information Bulletin Number 3, June 2005, by Carolyn Dimitri, Anne Effland, and Neilson Conklin):

Also, Angus Maddison’s Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD (2007, pp76-77) notes that “British farm employment fell from 56 per cent of the work force in 1700 to 1 per cent in 2003…. In the seventeenth century a majority of the population produced their own food, milked their own cows, made their own butter and cheese, and baked their own bread.”

Page 21: Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950, last name apparently pronounced “SHOOM-payter”) was a famous Harvard economist who popularized the phrase “creative destruction”; he also argued (as quote by Brad DeLong) that “depressions are not simply evils, which we might attempt to suppress, but…forms of something which has to be done, namely, adjustment to…change.” (See also this passage, which Paul Krugman frequently cites.) Also, the “life really is a beach” quote at the bottom of this page is a reference to chapter 10 of the micro cartoon book.

Page 21: The joke about the robot driver was in part inspired by an article about robot chefs (“Just like Mombot used to make“, NY Times, Feb 23 2010; see hilarious videos of the Snackbot, the Japanese savory-pancake-making robot, and—to see how hard this is—the ham-and-cheese-omelete-making robot). Of course, it now turns out that Google is working on a self-driving car. You can also play Trivial Pursuit against IBM’s Watson or (even more infuriating) play Rock-Paper-Scissors against a computer. PS. The joke about robot drivers is of course not entirely a joke: companies can go bankrupt if they cannot add value to the economy, and the same is (at least in theory) true about human beings.

Page 22: I stole the joke at the bottom of the page from some high school students via their teacher, who gave a presentation at a California Association of School Economics Teachers conference about having students do skits about economics terms. If I find the students (or, more likely, the teacher) I definitely owe them a free copy of the book.

Page 26: For one view of the “natural rate of unemployment”, see Christina Romer’s “Jobless Rate Is Not the New Normal” (NY Times, April 9 2011).

Page 29: At the bottom, “get real” is a reference to real business cycle theory. The line about whether the Great Depression was really a Great Vacation is frequently used to mock real business cycle theory, for example in Paul Krugman’s “How did economists get it so wrong?” (NY Times, Sept 2 2009).

Page 30: Peter A. Diamond, Dale T. Mortensen, and Christopher A. Pissarides won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Economics “for their analysis of markets with search frictions”.

Chapter 3: Money (pages 31-44)

Summary in haiku form

Summary in one paragraph

TBD

Notes on specific pages

Page 33: The “giant stones” used as money refers to the island of Yap.

Page 34: “Super-neutral” is a technical term that doesn’t mean the same thing as “neutral”, and its use here is somewhat misleading, but the cartoon opportunity here was too great to pass up 🙂

Page 35: David Hume (1711-1776), a friend of Adam Smith, wrote “Of money” in 1752: “Money is… only the instrument which men have agreed upon to facilitate the exchange of one commodity for another. It is none of the wheels of trade: It is the oil which renders the motion of the wheels more smooth and easy. If we consider any one kingdom by itself, it is evident, that the greater or less plenty of money is of no consequence; since the prices of commodities are always proportioned to the plenty of money…” However, Ed Dolan writes in his book (Introduction to Microeconomics, 4th edition; BVT Publishing; $39.99) that Hume’s view was actually more nuanced:

Eighteenth-century economists widely agreed that an increase in the money stock—chiefly gold and silver coins at the time—would raise the price level. Price increases had been Spanish began bringing gold back to Europe from the New World. A less settled question was whether an increase in the money stock would also “stimulate industry”—that is, cause real output to increase. Today we would say that the issue concerns whether or not money is “neutral.”

On that subject, Hume says that although an increase in the price of goods is a “necessary consequence” of an increase in the stock of gold and silver, “it follows not immediately.” The change in the money stock does not affect all markets at once: “At first, no alteration is perceived; by degrees the price rises, first of one commodity, then of another; till the whole at last reaches a just proportion with the new quantity of [money].” Agreeing with the modern theory that the stimulus to real output during this phase is only temporary, Hume continues: “In my opinion, it is only in this interval or intermediate situation, between the acquisition of money and the rise of prices, that the increasing quantity of gold and silver is favorable to industry.” In Hume’s view, there is no long-run effect on real output. In the long run, unlike the short run, money is neutral. A one-time change in the quantity of money has a lasting proportional effect on the price level but on nothing else.

Page 39: The “punch bowl” line is usually attributed to mid-1900s Fed chairman William McChesney Martin, Jr, but in fact he simply popularized the idea; the journalist who originally came up with the idea remains unknown.

Page 40: Central banks generally use government bonds but this “Ask Dr Econ” column from the San Francisco Fed addresses the question of “What will happen to the Fed if the national debt is paid off? Could the Fed buy precious paintings in the open market, instead of using Treasury debt to implement monetary policy?” That’s from 2001, when—yes!—people worried that the federal government might pay off the national debt!

Chapter 4: Inflation (pages 45-58)

Summary in haiku form

Summary in one paragraph

TBD

Notes on specific pages

Page 45: These lyrics are from Merle Hazard’s YouTube song “Inflation or Deflation?”

Page 46: The Bureau of Labor Statistics has a handy CPI Inflation Calculator. And here’s a graph of the CPI since 1913 (based on BLS data).

Page 47: On the challenges of actually calculating inflation, see this BLS FAQ: “When the cost of food rises, does the CPI assume that consumers switch to less desired foods, such as substituting hamburger for steak?” A more detailed analysis is in the Boskin Commission Report of 1996.

Page 48: Milton Friedman won the 1976 Nobel Prize in Economics “for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy”. Regarding “Whip Inflation Now“, this was a real campaign by President Ford in 1974.

Page 49: The concerns about deflation go back at least as far as Irving Fisher’s 1933 paper “The debt-deflation theory of Great Depressions“. Fisher was one of the most famous economists of the early 20th century and will be remembered for the Quantity Theory of Money (and also for noting, shortly before the stock market crash of 1929, that “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.”)

Page 54: On hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, see “How bad is inflation in Zimbabwe?” (NY Times, May 2 2006), “As Inflation Soars, Zimbabwe Economy Plunges” (NY Times, Feb 7 2007), “Life in Zimbabwe: Wait for Useless Money” (NY Times, Oct 1 2008), and “Zimbabwean Inflation Reaches 531 Billion Percent” (NY Times Economix blog, Oct 3 2008). Here is a picture of a 100 trillion Zimbabwean dollar bill!

Page 56: On what the appropriate inflation target should be, see Blanchard et al. 2010 (“Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy“, IMF Staff Position Note): “Should policymakers therefore aim for a higher target inflation rate in normal times, in order to increase the room for monetary policy to react to such shocks? To be concrete, are the net costs of inflation much higher at, say, 4 percent than at 2 percent, the current target range? Is it more difficult to anchor expectations at 4 percent than at 2 percent?”

Page 58: On the apparently positive benefits of small amounts of alcohol consumption by adults, see the citations on this Wikipedia page, especially O’Keefe et al, 2007 (“Alcohol and cardiovascular health: The razor-sharp double-edged sword”, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 50:1009-1014). The abstract notes that “light to moderate alcohol consumption (up to 1 drink daily for women and 1 or 2 drinks daily for men) is associated with cardioprotective benefits, whereas increasingly excessive consumption results in proportional worsening of outcomes… The ethanol itself, rather than specific components of various alcoholic beverages, appears to be the major factor in conferring health benefits.” Why is this called a “razor-sharp double-edged sword”? Because drinking alcohol can be addictive and, for example, over 10,000 people die each year in crashes involving drunk driving; drinking too much is bad for your liver too.

Chapter 5: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (pages 59-72)

Summary in haiku form

Summary in one paragraph

TBD

Notes on specific pages

Page 62: Value-added is also the basis of the value-added tax that is a major source of government revenue in many countries (but not in the U.S.).

Page 63: Simon Kuznets won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Economics “for his empirically founded interpretation of economic growth which has led to new and deepened insight into the economic and social structure and process of development”. Richard Stone won the 1984 Nobel Prize in Economics “for having made fundamental contributions to the development of systems of national accounts and hence greatly improved the basis for empirical economic analysis”.

Page 64: Health care spending as a percentage of GDP comes from the OECD; size of government spending (federal, state, and local) as a percentage of GDP also comes from the OECD (choose “United States” on the left hand side, then search the page for “general government expenditures”; click on the icon at the far right to download a table comparing various countries; we’ll come back to this in the next chapter); federal debt as a percentage of GDP comes from the OMB, Table 7.1.

Page 67: Here’s the NBER list of U.S. recessions; scroll down for the formal definition of a recession. The “just resting” line is a reference to Monty Python’s hilarious “dead parrot” routine.

Page 68: The “story of Japan” can be found, for example, in the data from the Penn World Table. (You have to hunt around for it, sorry.)

Page 69: Angus Maddison’s Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD (2007, pp157-164) provides a good overview on China:

In 1300, it [China] was the world’s leading economy in terms of per capita income… By 1500, western Europe had overtaken China in per capita real income, technological [sic], and scientific capacity. [From p164: “In 1792-3, Lord Macartney spent a year carting 600 cases of presents from George III. They included a planetarium, globes, mathematical instruments, chronometers, telescopes, measuring instruments, plate glass, copperware, and other miscellaneous items. After he presented them to the Ch’ien-lung emperor, the official respond was ‘there is nothing we lack… We have never set much store on strange or ingenious objects, nor do we need any more of your country’s manufactures.'”] From the 1840s to the middle of the 20th century, China’s performance actually declined in a world where economic progress elsewhere was very substantial. In the past half-century, China has been transformed in a catch-up process which seems likely to continue in the next quarter century.

On the dismissal of Britain as a “handful of stones in the Western Ocean”, see “Percy Cradock“, The Economist, Feb 11 2010, or this page view from Simon Winchester’s Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire (1985), which attributes the quote to “Xu Ji Yu, a scholar of the nineteenth century”. “Socialism with Chinese characteristics” refers to China’s self-described economic system (see also here); the famous quote from Deng Xiaoping about capitalism versus communism is that “I don’t care if it’s a white cat or a black cat. It’s a good cat as long as it catches mice.” Finally, data on growth in China’s real GDP per capita is not as clear as it could be, but the historical figures come from Penn World Table. For somewhat different numbers and projections, see Angus Maddison’s Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD

(2007) and Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, 2nd Ed.

(2007).

Page 70: “Telling a story with numbers” is a reference to a terrific piece of economics humor (“The conference handbook”, Journal of Political Economy 85:441-43, 1977) by George Stigler, winner of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Economics “for his seminal studies of industrial structures, functioning of markets and causes and effects of public regulation”. “The conference handbook” is an economics version of a joke that Stigler describes in his article:

There is an ancient joke about the two traveling salesmen in the age of the train. The younger drummer was being initiated into the social life of the traveler by the older. They proceeded to the smoking parlor on the train, where a group of drummers were congregated. One said, “87,” and a wave of laughter went through the group. The older drummer explained to the younger that they traveled together so often that they had numbered their jokes. The younger drummer wished to participate in the event and diffidently ventured to say, “36.” He was greeted by cool silence. The older drummer took him aside and explained that they had already heard that joke. (In another version, the younger drummer was told that he had told the joke badly.)

The percentage of China’s population living on less than $2 a day in 2005 comes from the World Bank.

Page 71: The quote at the top of the page is from Simon Kuznets. (Original source here.) More about the Human Development Index here and here. Real GDP growth in the U.S., going back to 1929, is available from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Questions about the value of GDP in rich countries can be found in, e.g., “The great GDP swindle” by Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, who (along with fellow Nobel-winner Amartya Sen) headed up a Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (report here, see also “Emphasis on Growth Is Called Misguided“, NY Times, Sept 22 2009). Another view comes from “Is GDP a satisfactory measure of growth?” by the OECD’s François Lequiller. (PS. I want to say that the story about being able to double GDP by having everybody work 80 hours a week comes from Paul Samuelson, but I’m not sure that it does…)

Page 72: Per capita GDP figures come mostly from 2007 figures from Penn World Table. Another good source (with slightly different numbers) is the “economy” section of the CIA World Factbook country profiles.

Chapter 6: The Role of Government (pages 73-86)

Summary in haiku form

Summary in one paragraph

TBD

Notes on specific pages

Page 79: The joke about “my normal weight is 20 pounds overweight” comes (if I remember correctly) from a routine by Abbott and Costello; the weight joke isn’t included in most excerpts, which only include the famous “Who’s on First” part of the routine.

Page 82: James Buchanan won the 1986 Nobel Prize in economics “for his development of the contractual and constitutional bases for the theory of economic and political decision-making”. More about public choice theory is here; I also recommend Mancur Olson’s book The Logic of Collective Action (1971).

Page 83: “Supply-side economics” is often used in a narrow sense to refer to the Laffer Curve idea that taxes are so burdensome that lower tax rates will increase revenue by stimulating economic activity, but we’re using it in a general sense to refer to the focus on the supply side of the economy (as opposed to the Keynesian focus on the demand side). A good read is Bruce Bartlett’s “How Supply-Side Economics Trickled Down” (NY Times, April 6 2007). Also, the “don’t do something; just stand there” line is adapted from Julian Simon, who uses it in the context of environmental issues; we’ll come back to these (and to Simon) in chapter 14.

Page 84: The joke about “12 to 1 I’ll never make it” once again (if I remember correctly) comes from a routine by Abbott and Costello; the joke isn’t included in most excerpts, which only include the famous “Who’s on First” part of the routine. Also, as on p64 the figures on size of government spending (federal, state, and local) as a percentage of GDP comes from the OECD (choose “United States” on the left hand side, then search the page for “general government expenditures”; click on the icon at the far right to download a table comparing various countries).

Page 85: The “jungle or zoo” metaphor comes (I think?) from Alan Blinder. In any case I didn’t come up with it 🙂

Page 86: The joke about “the doctor is five, the lawyer is three” is an old Jewish joke.